44

original

SUPLEMENTO

Otoneurología 2014:

comprendiendomejor los trastornos vestibulares

Actual.Med.

2014; 99: (791). Supl. 44-60

and, for instance in toxic or traumatic cases, can be unnoticed

until thepatient recovers fromother injures.

Ward et al (1) based their criteria for diagnosis of BVH

on the fulfillment of all of the following elements: presence of

visual blurring with head movement; unsteadiness; difficulty

walking indarkness or unsteady surfaces and in a straight path;

and symptoms being at least “abigproblem” andpresent for at

least1year, in theabsenceofotherneurologicconditionsoreye

pathologic conditions affecting vision.

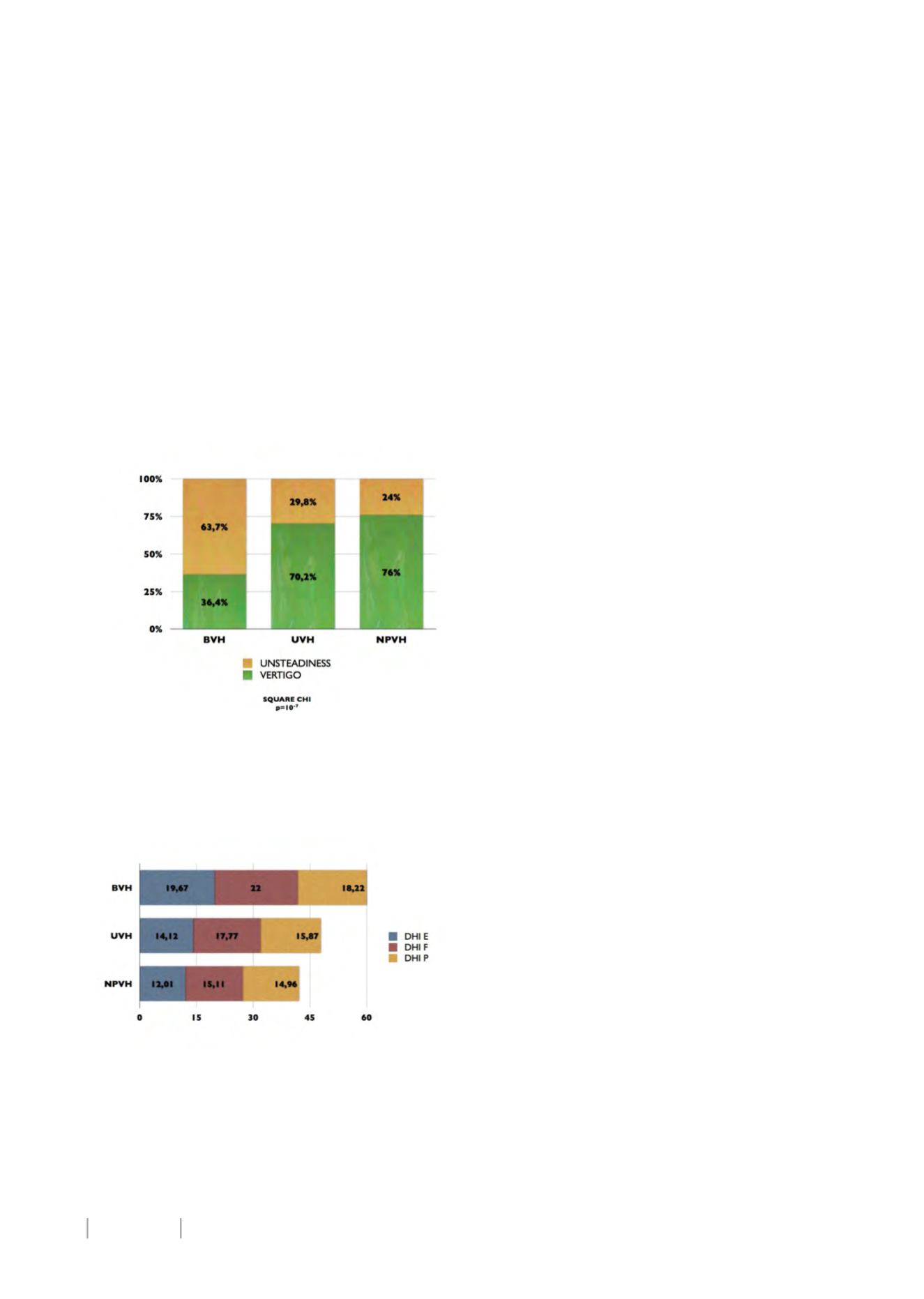

As seen in figure 2, most of the patients suffering from

BVH in our study population claimed to have unsteadiness as

main symptom, whereas the rest of the groups had anopposite

distribution. These differences were found to be statistically

significant (p=10

-7

for SQUARE CHI test). As for the temporal

course of symptoms, half of BVH patients (49,1%) described

a continuous sensation, albeit it worsened with movement.

UVH patients described a continuous sensation in amuch little

proportion (15,4%), and the same happened among NPVH

patients (11,1%). These differenceswere also found statistically

significant for the SQUARECHI test (p=10

-7

).

Figure2.Main symptomamonggroups

IMPACTONDAILY LIFE

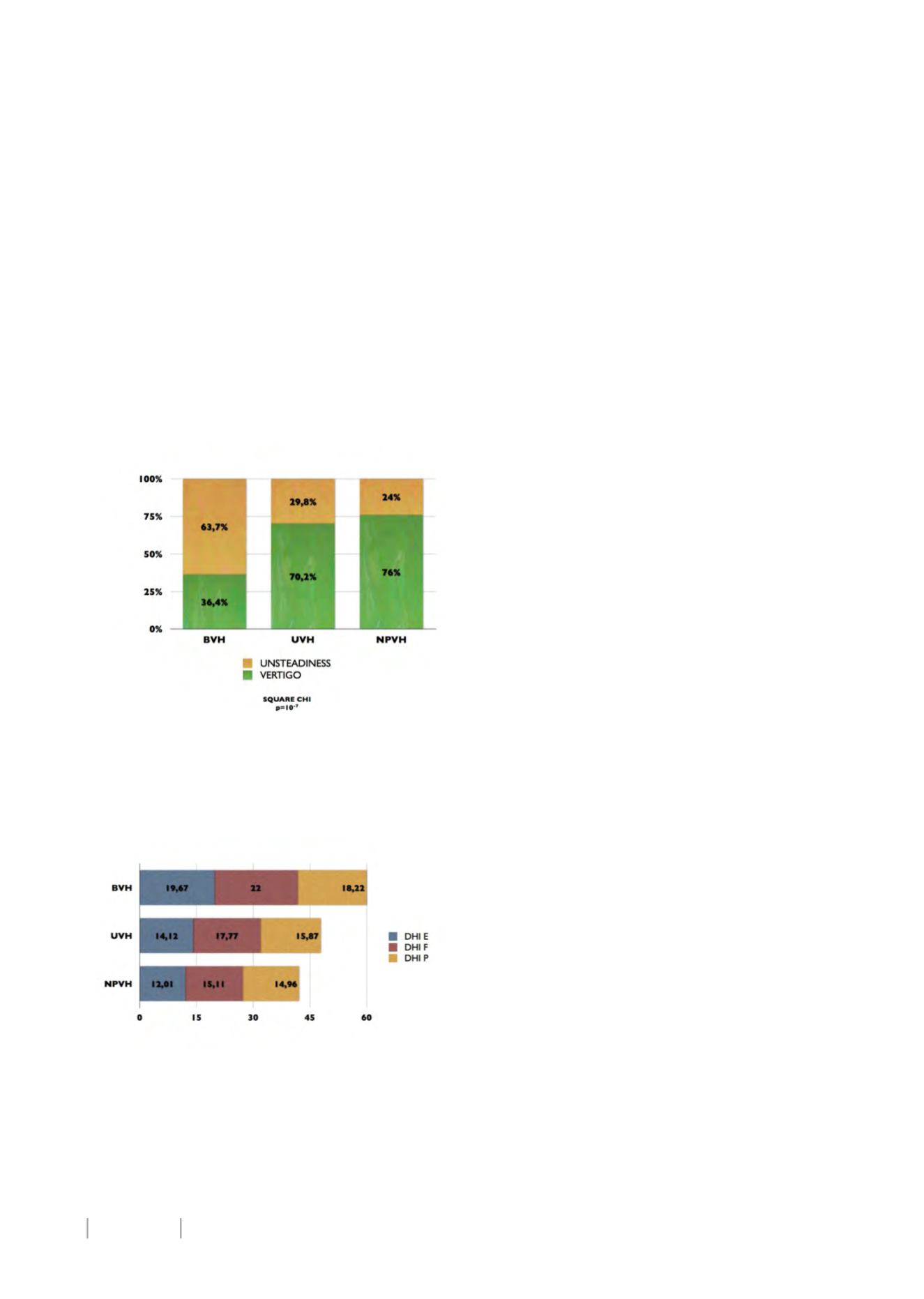

In figure 3 we represented mean scores for the Dizziness

Handicap Inventory (DHI) obtained ineachgroup.

Figure3.DizzinessHandicap Inventory scores

Emotional aspect of DHI was significantly worse (p=0,023

for Mann-Whitney test) among BVH patients than in UVH, and

also worse than among NPVH patients (p=0,001). In fact, all

the three components and the global score were significantly

different betweenBVH andNPVH groups (p=0,001 for functional

aspect and p=0,039 for physical aspect). As for UVH, differences

were statistically significant only for emotional component and

total score (p=0,043), addingnewevidence for assuming that the

findings described by Jáuregui-Renaud (13) and Gómez-Álvarez

(14) arenotonlypresent amongBVHpatients, but alsoappear to

be speciallymarked in this group.

Regarding daily impact, Ward et al (1) demonstrated an

increased risk of handicapped common activities, such as riding

on an escalator ormovingwalkway (odds ratio=8,1), going upor

down aflight of stairs (odds ratio=27,2-29,2), social activities like

visiting friends (odds ratio=11,5), or attending school or work

(odds ratio=19).

These authors also describe the finding of several other

difficulties related to improper use of visual or proprioceptive

confusing information, such as bumping when walking through

doorways or going through tunnels, and, specially, an increased

fall risk for these patients, as 87,8%had fallen in the last 5 years

because of their unsteadiness problem. In fact, age-adjusted fall

risk of their study population was 9 times greater than that of

otherdizzy respondentsand31timesgreater than their reported

national average.

DIAGNOSIS

Some considerations must be weighed when suspecting a

BVH, inorder to concludeonanaccuratediagnosis, evenwithout

any sort of assistant technology.

First, physiology and, most importantly, effect of the

vestibulo-ocularreflex (VOR)asgazestabilizermustbeaddressed.

When a normal VOR is present, head rotations are almost

instantly compensated by equal eye rotations in the opposite

direction. This system is extremelyefficient as its latency is about

10ms (14), and there is no possible substitution for this system,

if it is impaired, able to compensate headmovements in such a

short delay.

Thus, when VOR is not functioning correctly, eyes trend to

followhead at the beginning of its rotation, and afterwards, due

tovisual reflex, return tofixate the targetwitha rapidmovement

called saccade.

This saccade, that may be visible for the examiner, can be

used for diagnosis purposes, as it is a sensible sign of vestibular

loss (15).

As eyes drift from the target, it slips from the retinal

maximum visual acuity point for a moment, until drifting is

compensatedby the saccade, so, as adirect consequenceof VOR

impairment, there is a moment of blurry vision. This temporal

worseningofvisualacuitycanalsobeused fordiagnosispurposes,

asdescribedbyDemer andHonrubia (16).

Finally, it is not difficult to understand that, if no vestibular

information is available, balance without both visual and

proprioceptive inputs is not possible. This condition can be

achievedduring theperformanceof aRomberg test on foamand

witheyes closed (17).

PHYSICALEXAMINATION

These three considerationsweregathered ina recentpaper

authored by Petersen et al (18), who describes clinical diagnosis

of BVHasbasedon threebedside tests:

1.- Head impulse test (HIT):

firmly holding the head, the

examiner ask the patient to focus on a target and then, forces

fastpassive rotationsof theheadwithanapproximateamplitude

of 10-20º and, at least 120º/s. If VOR is working normally, eyes

move immediately on the opposite direction keeping focus on

the target, whereas, when VOR is impaired, head movement

towards theaffectedsidecannotbecompensated for suchabrisk

rotation, soeyes driftoff the target andmust performa catch-up

saccade. In thecaseofBVH, saccadescanbedetectedwhenhead

is rotated toboth sides.

Thereare two typesof saccades,dependingon their latency.

Saccades that occur within the rotation are called “covert”, and